Ana Petrović

visual artist

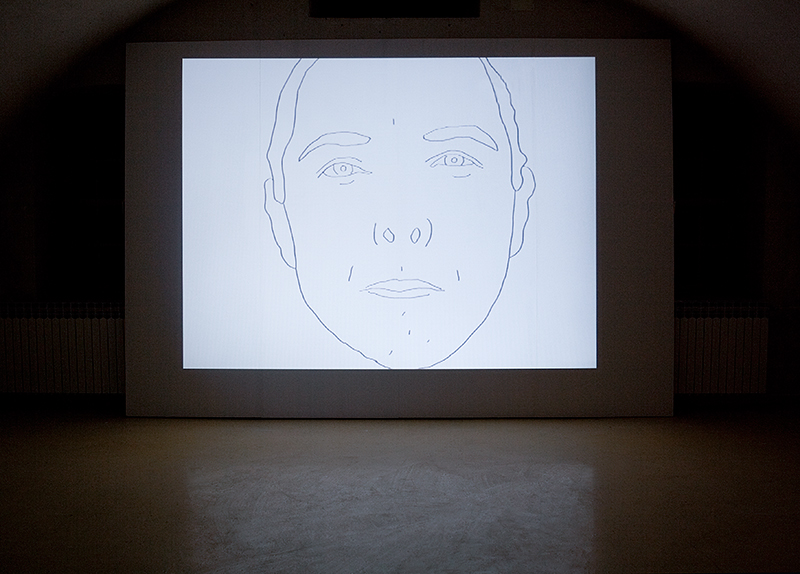

My Sin, I’m Guilty, 1:27 min in loop,

HD video, 2012

Moj grijeh, kriva sam, 1:27 min. u loopu, HD video, 2012.

Bez puštenog zvuka ponavljam moj grijeh kriva sam, jer grijeh je prljava mala riječ. Sv. Augustinu, ocu teorije o grijehu, išao je na živce beskrupulozan optimizam Rimljana. Pričamo o ocu ideje „istočnog grijeha“ u kojemu je Eva nagovorila Adama da zagrize u jabuku znanja a Adam, naivan kakav jest, zagrizao i sada svi nosimo žig vječno pomalo nastrane prirode. Po Augustinu, to je trenutak kada smo prestali biti sposobni uistinu voljeti jer smo toliko umotani u svoj ponos i egoizam, teško sami sebe razumijemo, strasti nas obuzimaju, lovimo fantome koje su stvorili naši strahovi i nesigurnosti. Augustin se podsmjehivao svim filozofima koji su dovoljno priglupi da bi uopće pomislili da se ovdje na zemlji može biti sretan i postići blaženstvo na temeljima vlastitog truda i rada.

Kada ovo sročimo ovako ukratko, pomislili bi kako je nemoguće da su ovakve misli ne samo preživjele, već imale višestoljetne sljedbenike. Iako u suštini tmuran pogled na svijet Augustin je propagirao duboko utješujuću misao- da su naši životi tužni i kaotični iz jednostavnog razloga što smo ljudi i sve što je ljudsko nikada ne može biti u potpunosti ispravno. Sposobni smo promišljati o ljubavi i vrlinama ali nismo sposobni da ih u potpunosti osiguramo za sebe. Iako zvuči depresivno, Augustinova filozofija je ipak duboko darežljiva spram siromaštva, neuspjeha i poraza, naših i tuđih. I ne moramo biti kršćani da bi mogli vidjeti prednosti ovakvog razmišljanja koji stoje kao podsjetnici na neke od opasnosti i okrutnosti koje dolaze iz vjerovanja da život može biti usavršavan do savršenstva ili da apsolutna nevinost postoji.

Augustin je svojim teorijama pomirio puno toga, ali primarna ideja koja ga je vodila pri formiranju i usustavljivanju je pitanje dualizma u priči o jabuci. Zmiju se interpretiralo kao Sotonu, drugo naličje Boga, protutezu Bogu. Dakle, bog sam po sebi. Kako je kršćanstvo monoteistička religija zmiji se trebala oduzeti moć a krivnju svaliti na glupavu Evu i povodljivog Adama. Ili, konkretnije rečeno, pomirba se dogodila kada je Augustin zaključio da zlo ne postoji samo po sebi. Udarac dualizmu. No, stavimo to u perspektivu: roditelj koji oplakuje smrt svog djeteta. Probajte njemu objasniti da ta bol nije stvarna, već samo odsustvo dobroga.

Ako pak, čitamo kršćanske portale vrlo brzo ćemo naići na članke prema kojima je čak i osjećaj krivnje grijeh jer je usko vezan uz stid kojega su Adam i Eva osjećali nakon što su pojeli jabuku znanja. Drugim riječima, griješi i osjećati ćeš se krivim. Osjećaj se krivim i tu si zgriješio. I tako je ideja koja je trebala utješiti u svojoj ograničenosti postala beskonačno moraliziranje koje čini ljude malima kroz teološku kastraciju. Zato nije neobično danas čitati članke o istočnom grijehu i njezinoj filozofiji kao poticatelju anksioznosti i pojačivaču osjećaja krivnje koji nudi ponižavajuću sliku o samome sebi serviranu na tanjuru razočaranja.

Grijeh je, naravno, konstrukcija određenog društva u određenom trenutku. Nekada davno pripadnici crkve bi kamenovali vlastite članove ako bi majka i otac izjavili da im je sin pijan i buntovan, radi časti obitelji. Danas nitko ne bi pokušao opravdati takve postupke, no nekada oni su bili norma.

Grijeh je uska i ograničavajuća riječ za čitav niz imenica koji bi trebali bolje objasniti moralna pitanja. Možda je zato bolje krenuti od toga što grijeh nije, i to primjerom. Ako bi se lav našao na ulicama Londona i usmrtio pa potom pojeo čovjeka, kao što to lav zna i može, bi li rekli da je lav u grijehu? Ako je priroda lava da jede, pa i ljudsko meso, grijeh je nešto što je odmak od prirodnog stanja što je u suštoj suprotnosti od Augustinova objašnjenja. Kao riječ koja prvenstveno pripada teološkom shvaćanju svijeta grijeh podrazumijeva božanski diktat- ne prirodu čovjeka, ne odmak od boga, već praćenje popisa. No, ako u Bibliji piše da žene ne smiju imati tetovaže i nositi zlatne lančiće i pletenice, kako danas Crkva ne smatra to grijehom? Za Židove, naprimjer, još uvijek stoji zabrana nošenja tkanine koja je mješavina vune i lana, ali kršćani su negdje usput odlučili da to pravilo nije baš toliko bitno. Očito je koncept dobra i zla vrlo fluidan, čak i za kršćane. Dobar dodatni primjer bi bio ban Jelačić, za hrvate branitelj i junak, ali za Mađare, razumljivo, zločinac nakon što je postao odgovoran za tisuće smrti Mađara.

Grijeh je, dakle, uzaludni pokušaj pojednostavljivanja svijeta oko sebe, kao alat iznimno moćan ali nimalo sveobuhvatan i stoga opasan. I što nam onda preostaje? Nietzsche kada piše o Amor fati, odnosno ljubavi- ne trpljenju ili popravljanju- nego ljubavi prema vlastitoj sudbini, gledanoj unazad. Nietzsche misli da, ako želimo imati dobar život, trebamo imati na umu puno kontradiktornih ideja i savladati ih u onom trenutku kada postanu relevantni. U Nietzscheovim očima ne trebamo biti dosljedni. On nas, dakle, ne traži da biramo između snažnog fatalizma na jednoj strani ili krotkosti na drugoj. Ne želi da naša mentalna kutija sa alatom bude opremljena sa samo jednim setom ideja, nego sa više njih, jer čekić ne rješava sve situacije. Čak i kontradiktorne ideje su iskoristive, one u koje možda niti ne vjerujemo, ali su korisne zato jer funkcioniraju.

A što se tiče pitanja zla možda će ono zauvijek biti nešto poput odluke Vrhovnog suda o pornografiji, u S.A.D.-u, koji je nakon dugo muka zaključio definiciju: prepoznati ćeš ju kada ju ugledaš[1].

[1] Ron Rosenbaum, „The End of Evil“, The Spectator, 30.9.2011.

Without making a sound I repeat My sin, I am guilty, because sin is a dirty little word. St. Augustine, the father of the sin theory, was annoyed by the shameless optimism of the Romans. We are talking about the father of the idea of ”original sin,” in which Eve persuaded Adam to bite into the apple of knowledge and Adam, naive as he was, did so and now we all bear the mark of a somewhat crooked nature. According to Augustine, this is the moment we stopped being able to truly love because we got so wrapped up in our pride and egoism, we have a hard time understanding ourselves, our passions are overwhelming, we chase phantoms created by our own fears and insecurities. Augustine mocked all philosophers who were foolish enough to think that you could be happy here on earth and achieve bliss on the basis of one’s own work and effort.

Now that we’ve put it so succinctly, one would think it is impossible that such thoughts have not only survived, but gained followers throughout the centuries. Although essentially a gloomy outlook, Augustine propagated a deeply comforting thought – that our lives are sad and chaotic for one simple reason that we are human and nothing human can ever be completely right. We are capable of imagining love and virtue, but not fully able to secure them for ourselves. Although it sounds depressing, Augustine’s philosophy is nonetheless profoundly generous against poverty, failure and defeat. We do not have to be Christians to see the benefits of this way of thinking, which stands as reminder of some of the dangers and cruelties that come from believing that life can be eternally perfected or that absolute innocence exists.

Augustine reconciled a great deal of things in his theories, but the primary idea that guided him in shaping and framing them is the issue of dualism in the apple story. The serpent was interpreted as Satan, the opposite of God, the counterweight. So, god himself. Because Christianity is a monotheistic religion, power had to be taken away from the serpent, and blame placed on foolish Eve and gullible Adam. Or, more specifically, the reconciliation occurred when Augustine concluded that evil did not exist by itself. A blow to dualism. But let’s put it in perspective: a parent who mourns the death of their child. Try to explain to him that the pain is not real, only the absence of good.

If, however, we read Christian portals, we will soon find articles that say that even feeling guilty is a sin on its own merits because it is closely related to the shame of Adam and Eve after eating the apple of knowledge. In other words, make mistakes and you will feel guilty. Feel guilty and you’re in the wrong even there. And so the idea that was supposed to comfort narrow-mindedly gave way to infinite moralizing that makes people small through theological castration. That is why it is not uncommon to find articles today about original sin and its philosophy as anxiety-provoking and guilt-increasing, offering a humiliating self-image served on a plate of disappointment.

Sin, of course, is the construct of a particular society at a particular moment. Once upon a time, church followers would stone their own members if their mother and father declared their son was drunk and rebellious, in the name of family honor. Today, no one would try to justify such practices, but they used to be the norm.

Sin is a narrow and restrictive word for a whole range of nouns that should better explain moral issues. Perhaps this is why it is better to start with what sin is not, by using an example. If we were to find a lion on the streets of London and if he killed and then ate a human, as a lion is wont to, would we say that the lion is in sin? If it is the nature of a lion to eat, including human flesh, sin is then a deviation from a natural state, which is in stark contrast to Augustine’s explanation. As a word that belongs primarily to the theological conception of the world, sin implies the divine dictation – not the nature of man, not a departure from God, but violation of a set of rules. If the Bible says that women should not wear tattoos, gold chains and braids, how come the Church does not consider this a sin today? For Jews, for example, there is still a ban on wearing a fabric mixture of wool and linen, but Christians somewhere along the way decided that the rule was not so important. Obviously the concept of good and evil is very fluid, even for Christians. A good additional example would be Josip Jelačić, for Croats a defender of country and a hero, but for the Hungarians, of course, a war criminal after he became responsible for the deaths of thousands of Hungarians.

Sin, then, is a futile attempt to simplify the world around us, a tool extremely powerful but not at all comprehensive and therefore dangerous. And what, then, are we to do? Nietzsche writes about Amor fati, that is, loving – not enduring or improving –but loving one’s own fate. He thinks that, if we want to have a good life, we need to keep in mind a lot of contradictory ideas and master them as they become relevant. In Nietzsche’s eyes, we don’t need to be consistent. He does not, therefore, ask us to choose between strong fatalism on the one hand or meekness on the other. He doesn’t want our mental toolbox to be equipped with just one set of ideas, but more than one, because the hammer doesn’t solve all situations. Even contradictory ideas are usable, ones we may not even believe in, but are useful because they work.

And as for the issue of evil, it may forever be something like the Supreme Court’s decision on pornography in the US, which after a long ordeal concludes the definition: you will recognize it when you see it.[1]

[1] Ron Rosenbaum, “The End of Evil“, The Spectator, 30.9.2011